As part of a new series on conditions that may be overdiagnosed, Dr Toni Hazell considers the potential problems with breast cancer screening

Background

The UK breast screening programme has been running since 1988. Women are invited for a first mammogram between the ages of 50 and 53, and again every three years until the age of 70, after which they can opt into further screening. Trials are assessing whether the screening period should be extended – to start at age 47 and continue up to 73.1 Meanwhile there is public outrage over the lack of screening tests during the pandemic, and a petition is calling on the Government for more investment in the programme.2 One million people allegedly missed their screening during the pandemic, while an earlier IT failure meant that 450,000 weren’t invited.3

Reasons for overdiagnosis

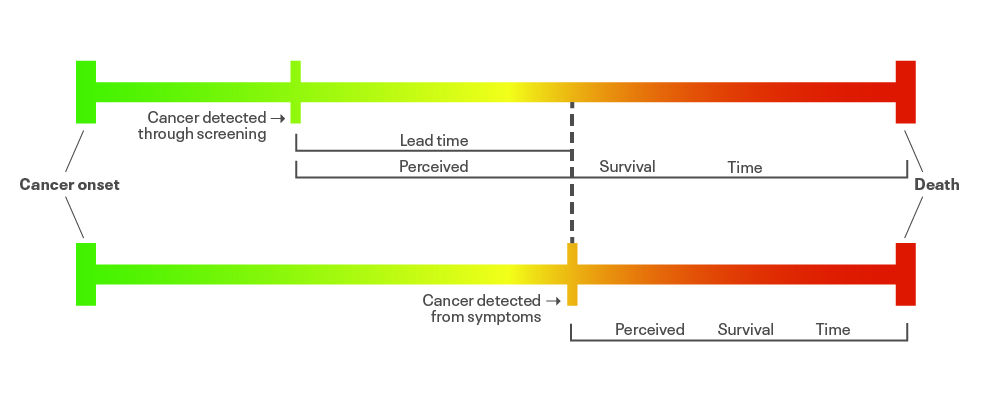

Before we look at breast screening specifically, let’s think about how screening can cause harm. Think back to statistics lectures at medical school, especially about lead-time bias. I’m 46. Let’s say that I currently have a cancer I don’t know about. If I develop symptoms at age 53, it looks quite indolent so I have a period of ‘watch and wait’ management, then I have surgery and chemo that works for a bit, then I die from the cancer at 65. My survival time will be 12 years. If I go for a full body scan tomorrow (age 46, remember) and the cancer is found, I have various treatments that work for a bit and then stop working, and I still die at 65. In that case, my survival time will be 19 years. That would be deemed a success – seven extra years of survival after diagnosis. But I’ve just swapped seven years of apparently healthy life for seven years of worrying about my cancer, and I’m not going to live any longer.

It’s important that screening programmes are shown to improve survival in reality, not just by the use of lead-time bias – that’s why the Wilson criteria for screening include the need for a recognisable early stage, and good understanding of the natural history of the condition and accepted treatment. Without these elements, we might just be replacing years of good-quality life with years of poorer-quality life.

Next, we need to consider the fact that not all cancer causes harm. Over the past few decades we have made amazing strides in reducing deaths from cardiovascular disease – average global life expectancy for CVD increased by more than six years between 2000 and 2019.4 We’ve all got to die of something and so diseases of old age such as cancer and dementia are inevitably going to increase. If we go looking for cancers that will never cause harm, overdiagnosis will happen.

For example, autopsy studies show that up to half of men in their 70s will have a focus of cancer in their prostate, but many of these cancers will be slow-growing tumours that would not have caused harm. The increase in unfocused PSA testing has raised concerns that many men are being diagnosed and are suffering from anxiety and unnecessary medical procedures.5,6

Finally, we need to remember that every test has a sensitivity and a specificity, which are generally less than 100%. A very sensitive test won’t miss anyone with the disease – but it will pick up some people who don’t have the disease. A very specific test won’t pick up any false positives – but it will miss some people who do have the disease. Improve the sensitivity of a test and the specificity is likely to drop, and vice versa – so a balance has to be found between the two. It’s difficult to know how many false negatives there are in the breast screening programme. It is described as a ‘very occasional’ event10 and has in the past been quantified as 0.2 per 1,000 women screened12, but false positives are another matter.

False positives

For every 100 women screened with a mammogram, around four will be told they need to have more tests, possibly including ultrasound or biopsy. That doesn’t mean that 4% of women screened have cancer – three out of those four will be reassured after those further tests that everything is fine and they can go back to the normal three-year recall, giving an approximately 1% pickup rate of cancer. Of course, some women will have been harmed by this process. They’ll have taken time off work for the appointments, have been anxious about the results, maybe had an iatrogenic infection or haematoma from a biopsy. Some might develop a more severe and ongoing health-related anxiety.

However, many people would say that all of these false positives are possibly a price worth paying given the number of lives that are saved. But would every woman with screen-diagnosed breast cancer have gone on to die from their cancer?

We have seen that increasing PSA testing might pick up men who would have remained blissfully unaware they had prostate cancer until they died of something else. Might this also be the case for breast cancer? Of the 1% of people diagnosed with breast cancer, one in five will have ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), where cancer cells are only found in the milk ducts. Since the early 1990s, the incidence of DCIS has trebled, whereas the incidence of invasive breast cancer has increased by about one-sixth. Much of this difference is presumably down to screen-detected disease.8 We don’t fully understand the long-term risks of developing invasive breast cancer from DCIS, or of dying from it, which means that women who have screen-detected DCIS are in a difficult position. And so are their doctors.

It’s psychologically tough to live with a cancer that you’re choosing not to treat, but for some women, treatment will cause more harm than benefit. A recent cohort study9 has looked at more than 35,000 women with screen-detected DCIS and identified that as a group they have a higher risk of invasive breast cancer and death from breast cancer than the general population. But the study acknowledges there will be some women for whom treatment might not be necessary – and further trials are needed to fully know who they are. Some such trials are currently under way, randomising women who are assessed to have low-risk DCIS to standard or non-operative management.9

How GPs can support patients

GPs don’t have much involvement in the breast screening programme, but sometimes a

woman will ask me if she should have a mammogram. Usually these women are well educated and have read about overdiagnosis. It’s difficult to know what to say, particularly if they want me to tell them whether or not to be screened. So I provide figures (see box, below).

In the end we all handle risk differently. People who arrive at the airport four hours before a flight might make different decisions from those who rock up just as the check-in desk is closing. As healthcare professionals the best we can do is to be honest about the benefits and risks of screening and hope our patients will be happy with the decisions they have taken.

What you can tell patients

When women ask my opinion, I give them these figures: for every 100 women who are screened, one life will be saved and three women will be treated for a cancer that would never have become life threatening.

So, for the 1,300 lives saved by the screening programme each year, 4,000 women are offered treatment that they did not need.10 The radiation from receiving a mammogram every three years between the ages of 50 and 70 will also cause a very tiny increase in the lifetime risk of cancer. I tell them that it’s up to them to use that information, and the accompanying patient leaflet10 to decide whether to have screening or not.

Dr Toni Hazell is a GP in north London

References

- NICE. What is the NHS Breast Screening Programme? 2022. Link

- Kum S. Invest to guarantee women’s access to breast screening – now and for the future. Petition 632824. 2023. Link

- Whitford P. In the NHS breast-screening scandal, the first priority must be the women. The Guardian 2018. Link

- World Health Organization. GHE: Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy. Link

- Jahn J, Giovannucci E, Stampfer M. The high prevalence of undiagnosed prostate cancer at autopsy: implications for epidemiology and treatment of prostate cancer in the Prostate-specific Antigen-era. Int J Cancer 2015;137:2795-802. Link

- Stangelberger A, Waldert M, Djavan B. Prostate cancer in elderly men. Rev Urol 2008;10:111-9. Link

- NHS England. Women urged to take up NHS breast screening invites. 2023. Link

- Cancer Research UK. Breast cancer statistics. Link

- Mannu G, Wang Z, Broggio J et al. Invasive breast cancer and breast cancer mortality after ductal carcinoma in situ in women attending for breast screening in England, 1988-2014: population based observational cohort study. BMJ 2020;369:1570. Link

- Public Health England. NHS breast screening: helping you decide. 2021. Link

- Office for statistics regulation. Statistical literacy: research. 2023. Link

- Marmot M, Altman D, Cameron D et al. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Br J Cancer 2013;108:2205-40. Link

- Science Direct. Lead time bias. 2013. Link

- Zhiyun G, Heitjan D, Gerber D. Estimating lead-time bias in lung cancer diagnosis of patients with previous cancers. Stat Med 2018;37:2516–29. Link