Analysis: GP Patient Survey lays bare stark regional inequalities

Cam Appel and John Ford of the Health Equity Evidence Centre analyse the data from the GP Patient survey to see what it reveals about socio-economic inequalities in primary care

The latest GP Patient Satisfaction Survey shows that overall patient satisfaction with general practice has improved slightly compared to 2023 but is still substantially lower than pre-pandemic levels. In the context of stark inequalities in quality, funding and workforce across the country: what does the data tell us about equity in patient satisfaction across the country?

Overall satisfaction

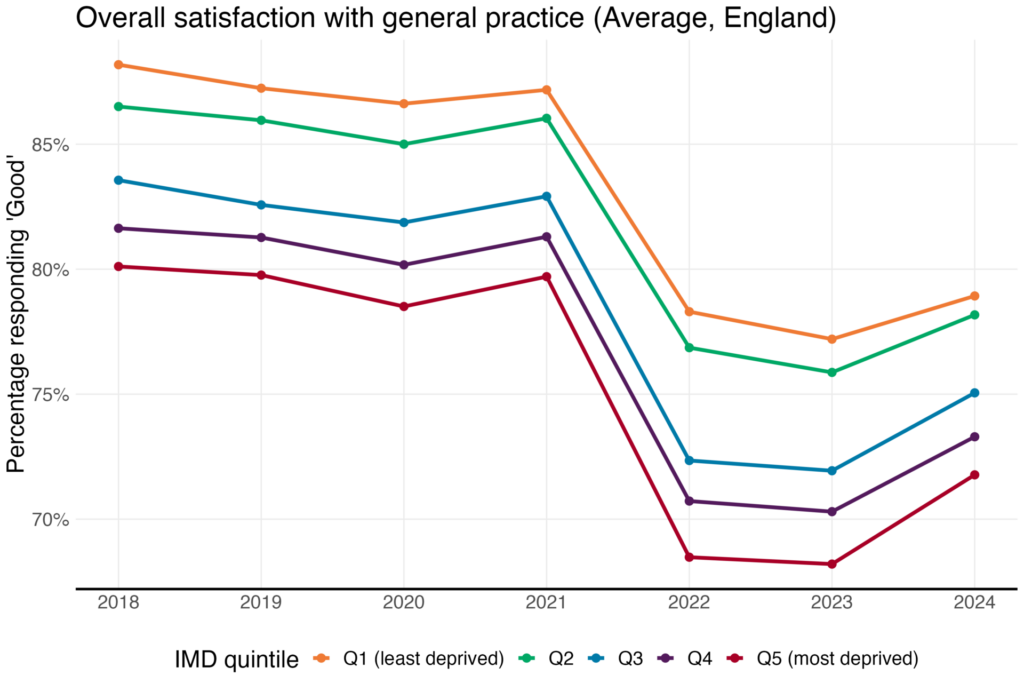

In the 2024 data, there remains a strong socio-economic gradient. 79% of patients who belong to practices in least deprived areas reported ‘fairly good’ or ‘very good’ overall experience, compared to only 72% in the most deprived areas. The gap has narrowed by 3% since an all-time high of 10% in 2022 and is now the same as the gap in 2017. It should be noted that the survey has changed to an online-first approach and there have been some small changes to the wording of the questions.

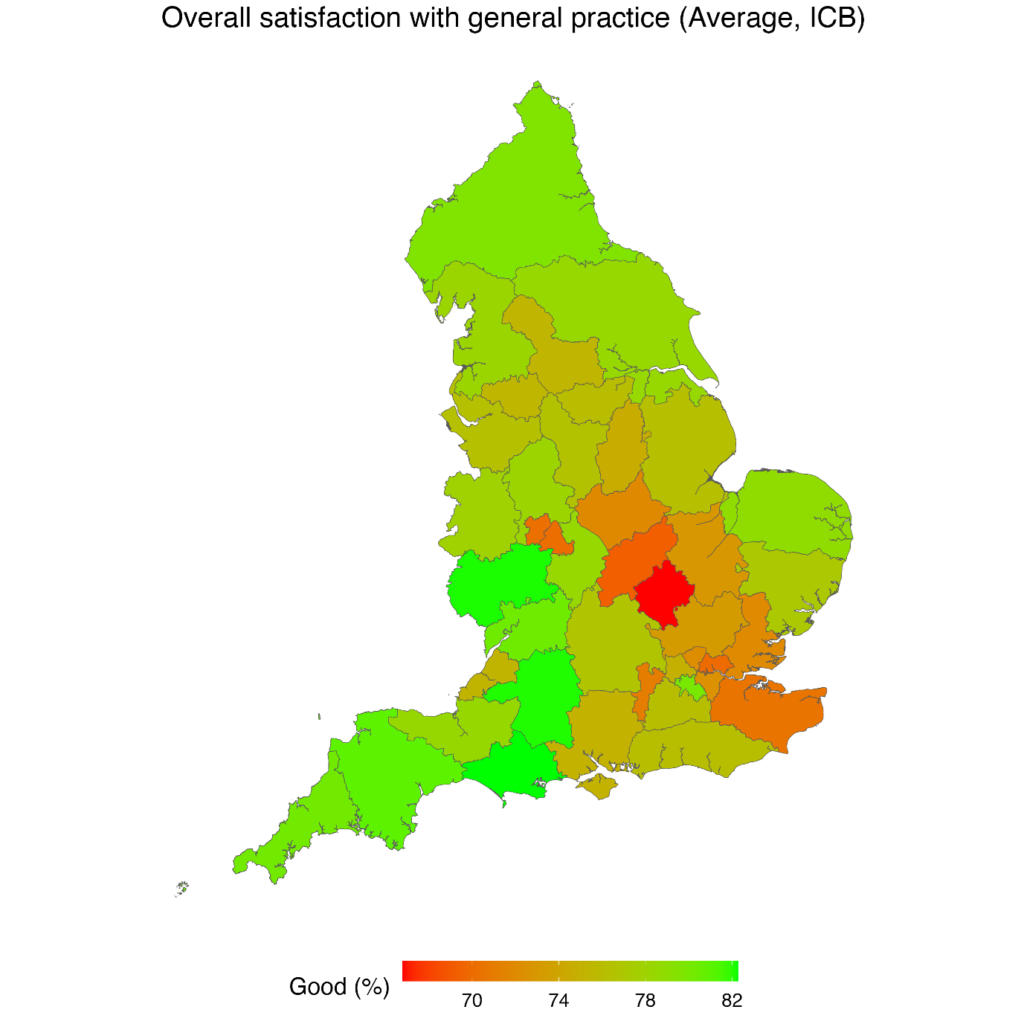

There are also large differences across ICBs. Dorset ICB had the highest average overall satisfaction in 2024 with 82% compared with Bedfordshire, Luton and Milton Keynes ICB with an average overall satisfaction of 67%.

There are also inequalities within ICBs. For example, in Shropshire, Telford and Wrekin ICB the overall patient satisfaction is relatively good (78%), but there is an 18% difference between practices in most and least deprived areas. However, in North East London ICB, there is relatively poor patient satisfaction (70%), but the difference between practices in the most and least deprived areas is relatively small. That lack of variation in North East London may reflect widespread socio-economic disadvantage within the ICB, compared to Shropshire, Telford and Wrekin which has a mixture of more affluent and poorer areas.

While the small improvement across all socio-economic groups and the narrowing of the gap is welcome, there is much further we need to go in improving patient satisfaction, standardising care, and narrowing socio-economic inequalities – particularly for some ICBs

Experience of contacting the surgery

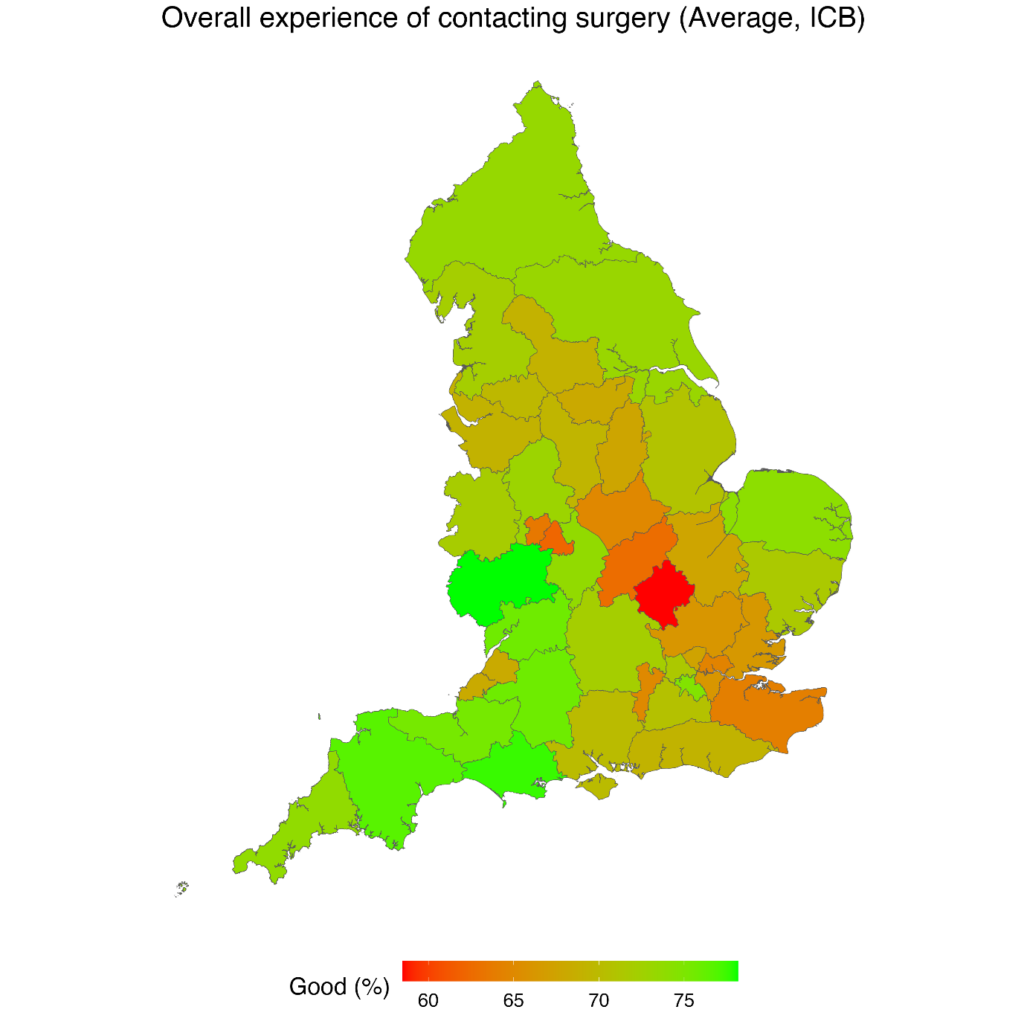

There are stark inequalities in patient experience of contacting the surgery. In 2024, only 65% of people in practices in the most deprived 20% report their experience of contacting the practice as good, compared to 73% in the least deprived area. The question has changed this year from making an appointment to contacting the surgery which makes the trend comparison less relevant. Herefordshire and Worcestershire ICB had the highest patient satisfaction when contacting the practice (78%), compared to Bedfordshire, Luton and Milton Keynes ICB (59%).

Continuity of care

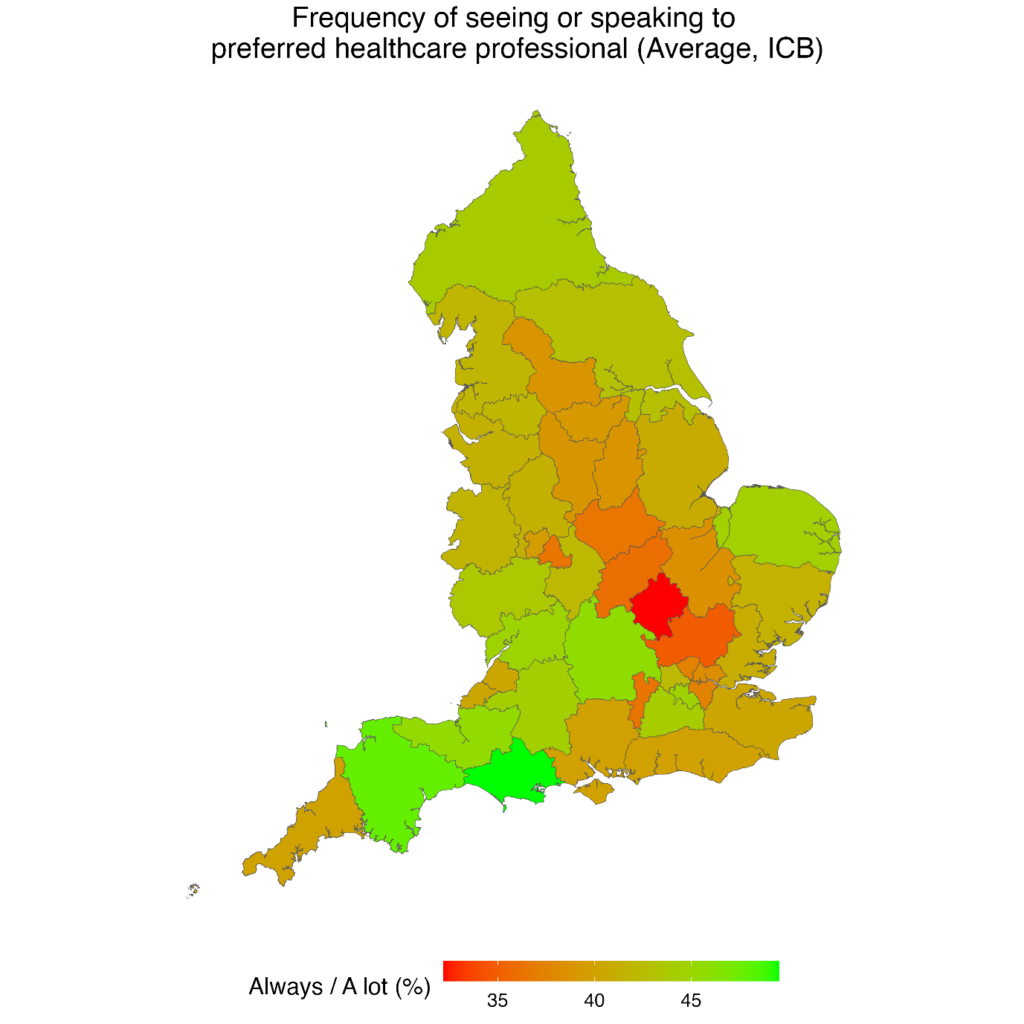

Patients in more deprived areas are less likely to see their preferred health professional compared to less deprived areas. The survey asks, ‘How often do you get to see or speak to your preferred healthcare professional when you ask to?’. Only 38% of patients in the most deprived areas respond always or a lot, compared to 44% in the least deprived areas. Overall continuity of care has improved since last year (from 35% in 2023 to 40% in 2024), although last year’s question asked specifically about seeing GPs.

However, there remain large differences across the country with Dorset ICB having the highest continuity of care (50%) and Bedfordshire, Luton and Milton Keynes ICB the lowest (32%).

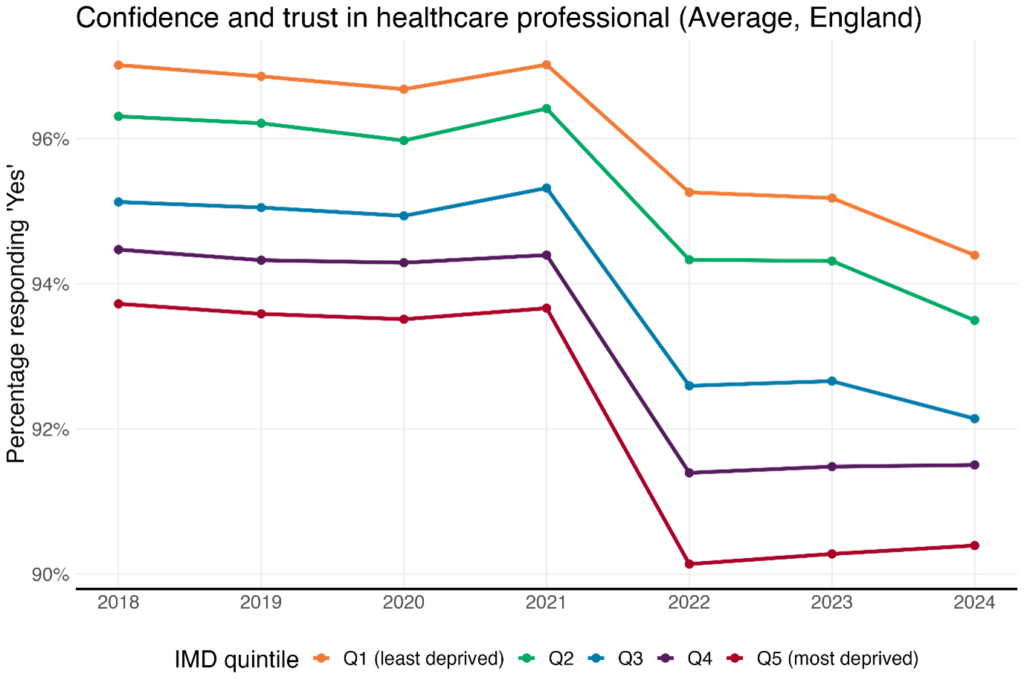

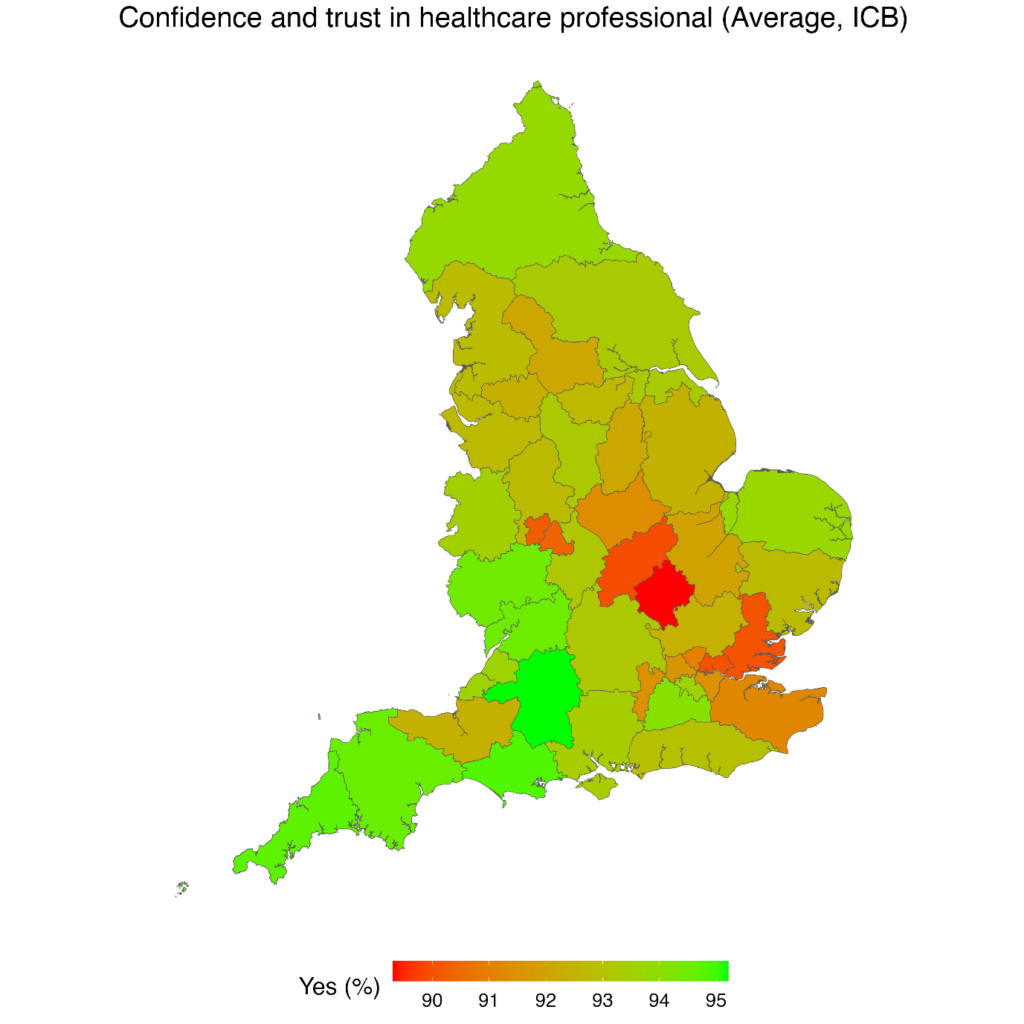

Confidence and Trust

Confidence and trust remain high, but socio-economic inequalities remain. 90% of patients in the most deprived areas responded ‘Yes’ when asked if they have confidence and trust in the healthcare professional they spoke to during their last GP appointment, compared to 94% in the least deprived areas. There has been a small decrease over time, but the drop has not been as large as other patient satisfaction metrics.

Patients in Bath and North East Somerset, Swindon and Wiltshire ICB had the highest trust in the healthcare professional (95%), compared to those in Bedfordshire, Luton and Milton Keynes ICB (89%).

Factors driving socio-economic inequalities in patient satisfaction

Some argue that inequalities in self-reported patient satisfaction need to be treated with caution because of differing expectations between groups. However, there is a consistent pattern with practices in more deprived areas having poorer Quality Outcomes Framework achievement and CQC ratings – inequalities in self-reported patient satisfaction are part of a wider pattern.

Underpinning inequalities in general practice is the unequal distribution of funding, workforce and workload. Practices in more deprived areas consistently receive less funding per weighted patient compared to less deprived areas and have fewer full-time equivalent GPs. Inequalities in funding and workforce are compounded by the additional time and resource practice staff need to help patients with complex socio-economic challenges.

Policies changes needed

We need a two-stream approach to addressing inequalities in the supply of general practice. Short- and medium-term initiatives which improve recruitment and retention of staff in practices in socio-economically disadvantaged areas are needed, with additional resources to help practices signpost and integrate to support an increasing volume of social problems, such as housing and welfare. Existing funding streams, such as discretionary ICB primary care funding, should acknowledge the additional time and resources needed for practices to achieve good outcomes in disadvantaged communities.

Over the long-term we urgently need to review the Carr-Hill formula to include deprivation and focus on achievement of outcomes rather than activity. This requires building expert analysis and consensus to ensure that practices which may already be struggling do not lose out.

Inequalities in patient satisfaction are not inevitable but require fundamental changes to the structures within general practice funding, workforce and workload.

Cam Appel is a data analyst at the Health Equity Evidence Centre, Queen Mary University of London

John Ford is the director at the Health Equity Evidence Centre, Queen Mary University of London

The Health Equity Evidence Centre is a new academic collaboration, hosted by Queen Mary University of London, that using machine learning to build the evidence base of what works to address inequalities and provides data insights.

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens

Related Articles

READERS' COMMENTS [3]

Please note, only GPs are permitted to add comments to articles

And smaller practices score far more highly than larger practices.

Exactly Peter and that’s why once again they will try to phase out smaller practices.

What we need is a radical shake up of general practice to make it ‘fit for the 21st century’. We need to close outdated and “cutie’ small practices and merge them into bigger units to offer “treatment at scale”. We need to move family Drs into expensive new buildings “in the community” where they can access lots of services that are usually offered in hospitals (like ultra sound and minor injury clinics). We must call these places ‘hubs”The definition of ‘in the community’ will generally be anywhere with dense residential housing, nowhere to park and terrible traffic congestion..because thats where people want to access their healthcare hub..right slap bang in the middle of someone else’s community. We need to get rid of GPs so people can access less stuffy people with less knowledge who are probably easier to talk to and most likely unlikely to play golf and cost less per hour. We need to stop primary care making ‘unnecessary referrals’ and provide information and advice by remotely by email instead. And anyone who wants to see a dermatologist needs to see a photographer instead, who’ll photograph anything of interest and email it to someone to look at on a computer screen 3 miles away..that way we can spend lots and lots on new digital technologies and nobody has to meet anyone in person..well not a medically trained person, well at least not a dermatologist anyway. And we must increase continuity. Because thats what the people want. Because its the bed rock of the NHS. A veritable jewel in its crown. Wonderful.