Pulse examines the media coverage of the inquest of a woman with ME as headlines abound blaming her GP. Maya Dhillon looks at the case and questions why these dangerous headlines are being used

This week an inquest has been taking place into the tragic death of a 27-year-old Exeter woman with myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) in 2021. Maeve Boothby-O’Neill had been suffering with the condition for more than half her life. Her chronic fatigue impacted her life immensely. In her final months she was housebound, and unable to sit up and chew.

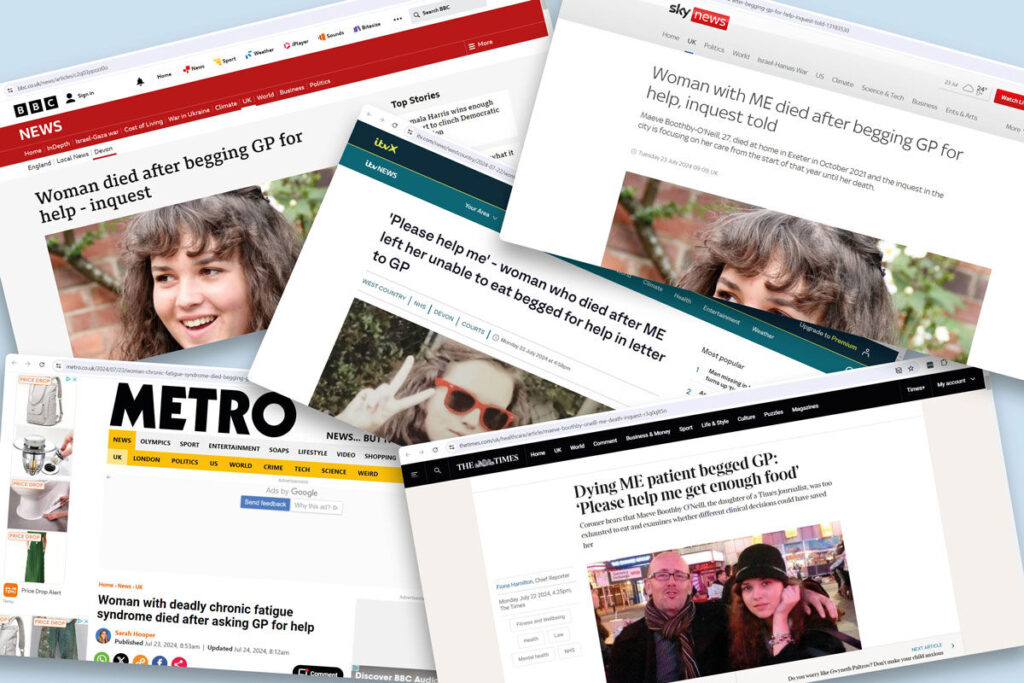

Looking at headlines from outlets such as the BBC, Sky News, ITV West Country, the Times and Metro, you would be forgiven for thinking that Maeve’s death was the fault of a callous or unbothered GP, given that they are all variations on: ‘Woman with ME dies after begging GP for help.’ A casual reader might think that Maeve approached her GP for support and had the door slammed in her face. However this could not be further from the truth.

The inquest is focussed on Maeve’s care from January 2021, until her death in that October. In those ten months she was admitted to the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital (RD&E) on three separate occasions (March, May and June), but discharged each time. In March she was discharged on the same day; after two weeks in May; and in June she was in hospital for almost two months.

The headlines are particularly focussed on the correspondences between Maeve and her GP – Dr Lucy Shenton of Barnfield Hill Surgery. In June, Maeve wrote: ‘I know you are doing your best for me, but I really need help with feeding. I do not understand why the hospital did not do anything to help when I went in. I am hungry, I want to eat. […] Please help me get enough food to live.’

At the start of the inquest, it was made clear that Dr Shenton had tried to get Maeve the help she needed repeatedly. She wrote to social services and NHS colleagues asking for someone to help, and not treat Maeve as a ‘medical outlier’.

Maeve passed away at home in Exeter on October 3.

Given Dr Shenton’s involvement in Maeve’s treatment, she was to be a key witness at the inquest. However, at the start of the proceedings, the coroner announced that she was too ill to attend. Dr Shenton was said to be suffering with PTSD over this case, and she felt that attending the hearing would ‘trigger a mental health breakdown.’ Through her own correspondence with Maeve, it was also clear the responsibility and sense of empathy that she felt. When Maeve was discharged from RD&E for the final time, Dr Shenton wrote in her notes: ‘If I could do anything I would, it’s breaking my heart.

Another GP from Barnfield Hill Surgery who was involved in Maeve’s treatment, Dr Paul McDermott, has spoken at the inquest. He expressed shock that Maeve was sent home from RD&E on the same day she was admitted, as she ‘ticked all the boxes for very severe ME.’ He continued that having read the notes sent to the practice, the hospital could not find a medical reason to keep her there.

The inquest, scheduled to finish next week, has shown no evidence that Maeve’s GPs did anything other than try their utmost best – and consistently go above and beyond their remit – to try and help her. Indeed, Maeve’s own father, a journalist at The Times, told the hearing that Dr Shenton had known Maeve for four years, was incredibly involved with her care and was ‘fond of Maeve’

None of these articles, in the body of the text, contradict that Maeve was well-supported by Dr Shenton and Dr McDermott. So why have well-respected news outlets run with a headline that suggests that Maeve’s GPs are the cause for her death?

Maeve’s case is undoubtedly a tragedy. Living with ME/CFS is incredibly difficult, and there is no cure. It requires dedicated and specific care – beyond the scope of general practice. All a GP can do with these patients is recognise the symptoms and refer them to secondary care in the hopes that they will get the support they need. Which is exactly what Maeve’s GPs did. At the inquest, Dr McDermott stated: ‘I was hoping someone would take it on and go into more depth with it. I realised as a GP we had run out of all options.’

GPs are not specialists, they are generalists. Dr McDermott told the hearing that he had not undergone specific teaching on ME/CFS, and suggested that other GPs might have an e-learning course for it, but that would be the extent of it, if any. If a GP follows care navigation protocol then they have done their bare minimum duty. As already stated, Maeve’s GPs repeatedly tried to get hospitals to look after her, begging colleagues to help them. GPs cannot be held to blame for the failure of secondary services. McDermott stated at the inquest: ‘We needed help. We all needed help. Maeve needed help.’

Are these headlines factually inaccurate? No. But do they tell the whole story? No. And are they a fair account of what happened? Absolutely not.

Maeve did beg her GPs for help, and they did try to help her, they themselves begging for specialised and coordinated care. Dr McDermott explained, ‘As GPs we are not experts and we rely on other people to help us out.’ Maeve was failed by other services – which, in turn, have been failed by a lack of funding. The hospital finally offered her IV administered nutrition before she died, which she said she would have accepted had it been an option presented to her earlier on. At this point though, she believed that this and further hospital admissions would only prolong her agony.

Dr Shenton told Maeve’s father that she had never seen ‘anyone so poorly treated as Maeve was.’ The case led to Dr Shenton developing PTSD, and that was before these vicious headlines, making her and Dr McDermott out to be the culpable villains in the story.

As stated before, the copy beneath the headlines in all these pieces is accurate. But leading with these headlines, draws readers into an anti-GP vortex which, in this case, is resolutely unfair and reckless reporting. Pulse screenshotted these headlines when we saw them, anticipating they would be taken down and changed following backlash. But, at time of publication, they remain to be up, which only highlights our point more.

A better and more accurate headline would have been: ‘Woman with ME dies after she begs GP for help, GP helps and secondary care fails.’ But hey – that’s not as catchy a news hook now, is it?