This site is intended for health professionals only

PCNs are forced to decide which targets are achievable in the new Network DES. Emma Wilkinson reports

The release of the long-awaited new Network DES on 31 March has left many clinical directors (CDs) taking a careful look at what they are able to achieve, bearing in mind the pressures they are under, the work required and the resource provided.

It comes with a potentially significant boost to funding through additional roles reimbursement scheme (ARRS) rises from £12.30 to £16.70 per patient and an increase in mental health roles as well as

a dramatic expansion to the investment and impact fund (IIF) from 389 to 1,153 available points at £200 per point achieved.

Yet while the IIF service specifications on cardiovascular disease prevention, care homes, cancer, personalised and anticipatory care are familiar to PCNs, the level of work required to achieve this new tranche of funding is not.

It includes three new indicators, which are being supported by £34.6m of funding focusing on prescribing of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and faecal immunochemical testing (FIT) as part of urgent referrals for suspected lower gastrointestinal cancer.

As always with PCN funding, the headline figures include a fair amount of caveat. The longed-for flexibility in ARRS roles has not materialised, and much of the core funding, including CD payments, has not moved at all, leaving PCNs to fund cost-of-living increases alone.

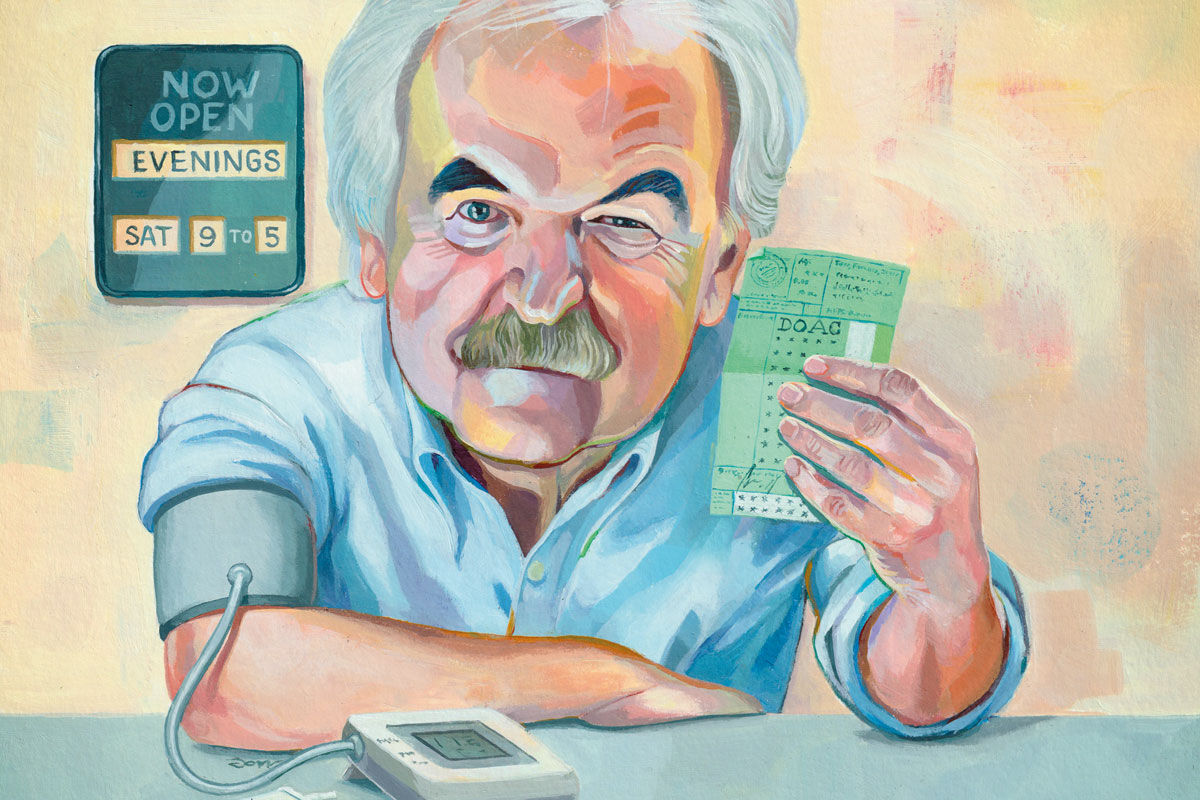

The aspect of the DES that caused the biggest stir was the compulsory requirement for PCNs to provide enhanced access between 6.30pm and 8pm Mondays to Fridays and between 9am and 5pm on Saturdays from October.

After repeated calls for clarification, it emerged that PCNs will have to provide appointments through the full period, not just within those hours.

Dr Laura Mount, CD at Central and West Warrington PCN in Cheshire, says she is still digesting what it means for them, especially what is possible with the IIF, and it’s taking time to process. ‘We’re trying our best but it’s huge.’

She is concerned about the extra pressure it will put on practices. ‘I can’t push my practices to breaking point. There is only so much I can ask them to do.’

Strategic approach

The prevailing view seems to be that the IIF will have to be approached strategically and pragmatically if PCNs are to avoid overstretching themselves for targets they are unlikely to meet.

Overall, the funding does not compare well with the amount of work that will need to be done, says Dr Emma Rowley-Conwy, CD of Streatham PCN in south London.

‘We’re going to have to evaluate each target and decide if it’s achievable for the money. Some of them we will decide not to do. It’s overwhelming how many things there are and it will be different from our approach to QOF which was just achieve, achieve, achieve.’

Dr Mount takes a similar view and is going through the indicators one by one: ‘I hope we’re already good on some of it. Other things we will do if they’re really important and will benefit patients because it’s the right thing to do. But there are some we know we may not achieve and we will have to resign ourselves to that.’

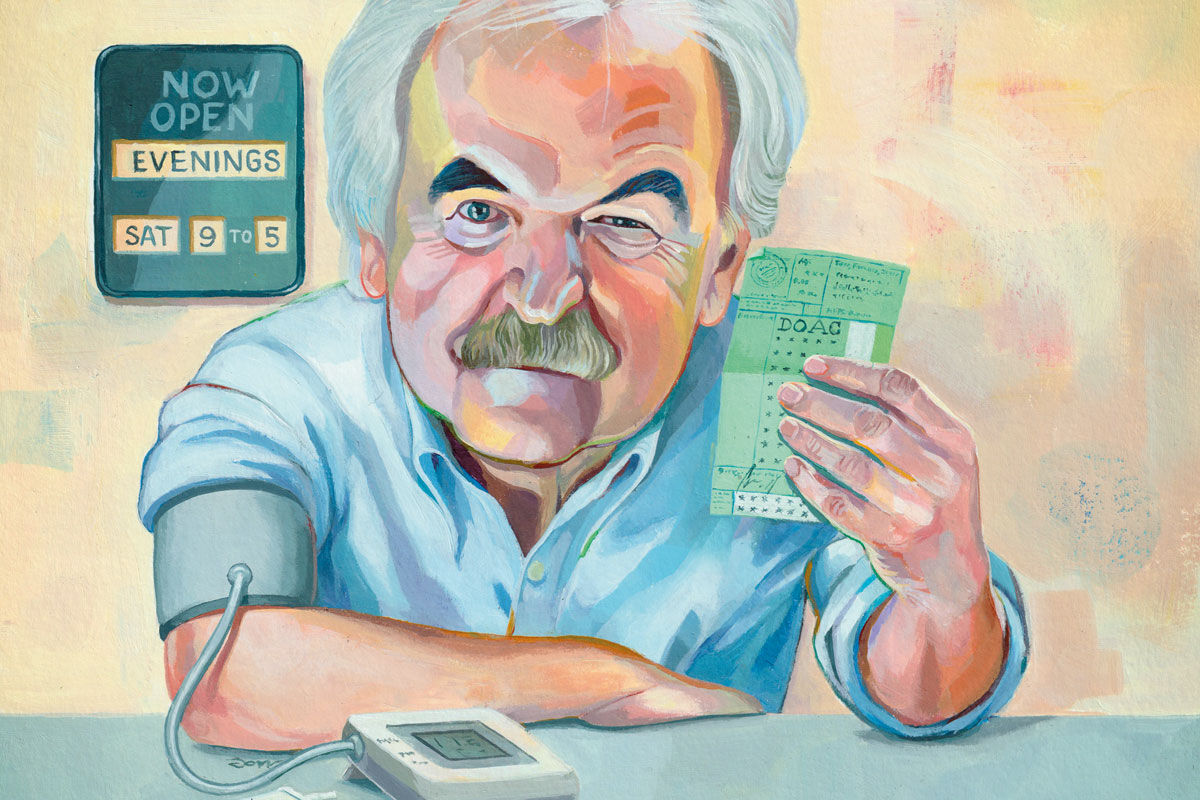

On cardiovascular disease, many PCNs have already done a lot of work on hypertension, buying additional blood pressure machines. Yet there are serious questions about whether it is appropriate to use the IIF to incentivise a switch of patients to a specific direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC), edoxaban, on cost grounds.

NHS England has now lowered the IIF thresholds from 40% and 60% to 25% and 35% after concerns from CDs that switching patients would be too much work.

Dr Sajid Nazir, CD of Viaduct Care PCN in Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, said GPs are used to CCGs asking them to do medicine switches. ‘You see this all the time, but then a year later the original drug comes off patent and is suddenly cheaper and you’re asking people to move back.

‘I’m not sure why it’s been moved into the PCN and it opens the door to other things. It is also a huge amount of work because it’s often not one consultation. There is a potentially large impact.’

What often isn’t considered is the extra work generated to achieve the indicators, he says.

‘The CVD targets are good in terms of picking up more people with hypertension to get them treated appropriately, but if you’re suddenly getting hundreds of people diagnosed together and you might not have ARRS staff to do that work it puts more pressure on services,’ he says.

There is also little acknowledgment of the work practices are already doing to catch up on chronic disease management and deal with post-pandemic demand, he adds. Their biggest worry is structured medication reviews taking up all of their clinical pharmacists’ time.

‘When you plot how many we need to do per week to achieve the indicators it’s huge and we wouldn’t be able to do it even if we employed more staff.’

He adds: ‘And what happens to all the rest of the work they have been doing on medicines management and chronic disease management? It’s give with one hand and take away with another.’

Some areas have been doing GP FIT testing to accompany cancer referrals for a while, making achievement seem simple on paper. But, says Dr Mount, they must be careful to ensure referrals are not delayed.

‘It seems to suggest that the result will have to accompany the referral, so we will need to have conversations locally about what that means. What I don’t want is a two-week-wait referral to be rejected or to sit for weeks on end with no one dealing with it.’

Dr Nazir raises the point that one issue they had locally even before this indicator was introduced was a shortage of FIT testing tubes. ‘We’re almost rationed already; we can’t get hold of them. So there’s a danger we’re going to start falling behind. I’m worried about this delaying referrals,’ he says.

Inequalities

While CDs are keen to tackle neighbourhood health inequalities there are concerns about whether the demands of the DES will get the desired results.

Dr Mount says that if the Government is ‘really serious’ about improving inequalities it ‘would look at where they really are, and fund work in areas of inequality’.

‘But instead they want you to look within your PCN. We enjoy doing this work. We have set up a service for housebound patients and do proactive care and we do a lot of hypertension and atrial fibrillation outreach work. We did lots of Covid outreach, and that’s enjoyable, but it’s inconsistent because each PCN is doing something very different and maybe there needs to be more sharing of learning.

‘We never know what to pick across the many things you could do. The health inequalities dashboard is often out of date, and we don’t have data analysts,’ she adds.

Dr Nazir says, ‘With health inequalities, on the surface, [for example] with the flu [IIF indicator] for adults we it do anyway and we learnt a lot from Covid vaccinations about recall and getting through to people so that’s not a massive concern. But flu vaccines for two to three-year-old children is something we have struggled with as a PCN – it’s been very hard to reach out.

‘The concern with this, along with some other indicators, like A&E attendance, is that you are exacerbating health inequalities despite doing tonnes more work. Patients don’t turn up or they keep going to A&E despite your efforts.

‘I’m not sure if the IIF is best for that sort of target because it doesn’t really address those issues or give solutions. More needs to be invested in education,’ he adds.

Workforce

Dr Partha Ganguli, CD of South Ribble PCN in Lancashire, believes workforce problems are a serious impediment to achieving IIF points. The increase in the ARRS is not necessarily for the types of staff they need, including nurses, and a significant chunk of funding in their area has not been taken up anyway.

‘If there was an opportunity to divert that money for general practice needs that would be the best option. There are lots of limitations including availability of workforce and flexibility,’ he says.

They too are concerned that their clinical pharmacists – who were employed to increase capacity – will be tied up trying to achieve targets.

‘We’re missing the fundamental point that they are there to improve access to care,’ he adds.

In Streatham, any increase in ARRS funding has already been swallowed by London weighting, explains Dr Rowley-Conwy. They have already avoided hiring mental health practitioners because they know it would be impossible to get staff.

Some of the difficulty PCNs might have in achieving targets is if they are already doing well in an area, for instance, access. They will struggle to show an improvement. ‘And it’s not because they’re doing badly,’ she adds. ‘It’s just badly worded.’

Dr Mount notes that getting ARRS roles in place, with training and supervision, has absorbed a huge amount of their core funding. ‘We have had to set up a quality committee to monitor the care they’re providing, patient experience and outcomes. We are like mini-CCGs.’ But CCGs had teams of people and experience in things like data analysis. ‘Everything seems to be falling to us.’

Dr Nazir says there’s been ‘no acknowledgment’ that there is a lot of catch-up work to do. ‘We should have had a year to reset,’ he says, adding that staff resilience and morale needs to be considered.

‘I’m glad we recruited our PCN manager a few months ago because it is a full-time job to keep on top of all this,’ says Dr Nazir. ‘I’m not sure how PCNs are doing this if they don’t have dedicated staff.’