Tiverton GP Dr James Wood, who has a special interest in dermatology, considers this unusual presentation in the latest of our ‘Once in a Lifetime’ series

What is it?

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) is a severe dermatological reaction that is widely considered a dermatological emergency. It causes widespread, painful blistering of the skin and mucous membranes associated with fever and potentially leading to dehydration, sepsis, organ failure and death.

SJS is now thought of as being at the milder end of a spectrum of disease, when less than 10% of skin is involved. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is the more severe form, when greater than 30% of skin is involved. SJS/TEN overlap syndrome occupies the crossover between 10 and 30%. In the early stages, however, the presentation of SJS, SJS/TEN overlap and TEN can be very similar.

How rare is it and what causes it?

SJS and TEN affects 1 to 3 people per million people per year in the general population. It is more common with advancing age and in Asian populations and slightly more common in women than men. It is more common in patients with SLE and HIV with some sources suggesting SJS can be as common as 1/1000 in patients with HIV.

In approximately 80% of patients affected, clinicians can identify a causative drug. This figure is higher in older patients.

More than 200 drugs have been reported to cause SJS, and it is thought that any drug has the potential to trigger it – particularly those with a longer half-life. The most common are anticonvulsants (notably lamotrigine and carbamazepine) and antibiotics (particularly penicillins, cephalosporins and sulphonamides). Allopurinol, NSAIDs and paracetamol are commonly implicated, too.

The usual onset when a drug is causative is from a few days to eight weeks after initiation, though repeat introduction of the offending drug will trigger symptoms faster.”

Other potential causes of SJS are malignancy, vaccinations and infections. Some genes are implicated in increased risk of SJS.

Clues for early detection

One of the difficulties for early diagnosis of SJS is that the nonspecific features tends to precede any rash, usually by several days. These symptoms are fever, myalgia, malaise, arthralgia, painful eyes and purulent cough. These are often thought of as being signs of infection and treated as such.

The appearance of a rash some days later is what usually raises the suspicion of SJS and it is at this stage that GPs will be referring urgently to secondary care. Depending on local arrangements this may be directly to dermatology or to medicine with dermatology input.

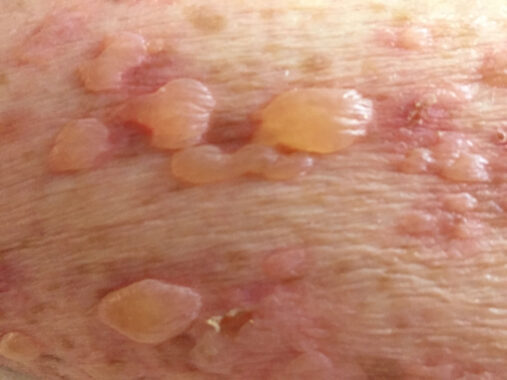

The presenting rash is typically erythematous and can appear as coalescing macules. In darker skin tones it may appear almost purple. These then develop into blisters or ulcerated areas which are more widespread and with more shedding of the skin in TEN than in SJS. Blistering may not be present at first presentation. Invariably the rash is painful but early on may be itchy.

As GPs we often see itchy rashes in patients with viral infections and most of the time this will not represent SJS. However, if you don’t think of it you won’t diagnose it and it is worth considering what drugs they have been on and how unwell they are. Other factors that lean towards a diagnosis of SJS are mucous membrane involvement, painful eyes and painful skin preceding the onset of rash. Mucous membrane involvement occurs in the majority of patients. This is usually around the mouth but can also be around the eyes and genitals. Mucous membrane involvement may not be present in the early stages of presentation.

May be confused with:

SJS can be confused with other drug reactions including drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Other potential diagnoses include:

- Staphylococcal scalded skin – particularly in children.

- Kawasaki disease

- Pemphigus and pemphigoid

- Erythema multiforme

The difficulty in the early stages of presentation prior to rash formation is misdiagnosis as infectious cause.

Red flags

GPs should be alert for painful rash in a patient with a prodrome of fever, especially if they have started a new medication within the last 8 weeks.

Usual treatment and prognosis

From a GP perspective, management is immediate cessation of culprit medications and emergency admission. Secondary care management is multidisciplinary, including dermatologists, ophthalmologists, intensivists, plastic surgeons and specialist nursing and is likely to take place in an intensive care setting. Management of fluid balance, shock, sepsis and organ failure is a priority. Patients require specialist supportive treatment and may benefit from input from tertiary care burns teams. Specific treatments include corticosteroids, cyclosporin, immunoglobulins and anti-TNF drugs.

The acute phase of the illness lasts up to 12 days. The sequelae may include optical problems, skin scarring and pigment change, contractures of soft tissues, respiratory complications, genital scarring and associated dysfunction and psychological problems. The mortality for SJS is approximately 5%; however this rises up to 40% in TEN. The SCORTEN score carried out in the first few days of admission can be used to asses prognostic risk in individual cases.

Dr James Wood is a GP with special interests in dermatology, surgery and emergency medicine