Once in a lifetime: Acoustic neuromas

Mr Gerard Kelly, consultant ENT and skull base surgeon at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, outlines this unusual presentation in the latest in our series of conditions that GPs may expect to encounter once in a lifetime

What is it?

An acoustic neuroma (more correctly termed a vestibular schwannoma) is a benign (non-cancerous) tumour that develops on the seventh cranial nerve (vestibulocochlear nerve). The cell of origin is the Schwan cell, not the neurone, and the nerve of origin is usually the vestibular nerve, so the term ‘acoustic neuroma’ is wrong on both counts, but the historic name, as they often do, has stuck. The tumour grows from the nerve sheath in the internal auditory meatus, which is a bony channel with the only opening medially, towards the brain. The tumour therefore can only grow medially into the cerebellopontine angle of the posterior cranial fossa and unchecked growth compresses the cerebellum and pons (of the brain stem).

How rare is it?

Acoustic neuromas are relatively rare, with an incidence of approximately 1 per 100,000 people per year. They account for about 8% of all intracranial tumours but 80% of tumours the cerebellopontine angle.

May be confused with…

Acoustic neuromas may be confused with other conditions due to overlapping symptoms.

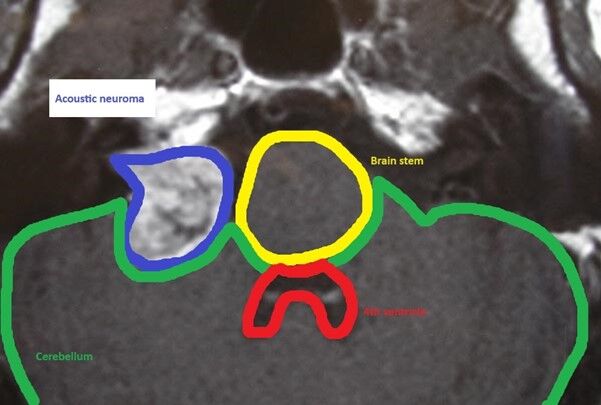

They are not usually confused on MR scanning, their appearance is characteristic, and mushroom like, with a ‘stalk’ in the internal auditory meatus and a ‘head’ in the posterior fossa.

A T1 MR scan right sided acoustic neuroma, with a stalk in the internal auditory meatus and a ‘head’ in the posterior cranial fossa, compressing the cerebellum. The tumour is ‘lit up’ by the administration of intravenous gadolinium contrast.

The symptoms of acoustic neuromas are unilateral hearing loss with ipsilateral tinnitus. While vertigo sometimes occurs, it is mild as the slow growing nature of the neoplasm allows compensation from the other ear’s balance system. The balance system is an integrated system. Hearing, on the other hand, is a devolved sense to each ear independently and a hearing loss in either ear can be identified readily.

Diagnostic competitors for hearing loss, tinnitus and vertigo are Meniere’s disease and labyrinthitis. However, more often such symptoms are attributed to aging. Of course both ears tend age at the same rate!

Red flags

Apart from unilateral deafness, tinnitus and imbalance, red flags are headache and visual loss (due to raised intracranial pressure), facial numbness (due to pressure on the trigeminal nerve) and swallowing problems due to pressure on the lower cranial nerves.

Clues for early detection

Patients with acoustic neuromas present with unilateral symptoms: sporadic acoustic neuromas do not occur bilaterally. Unilateral hearing loss and tinnitus are common in such cases, as is a mild imbalance (rather than rotatory vertigo). Numbness of the ipsilateral face suggests a larger tumour (with contact on the trigeminal nerve root).

NICE notes the criteria for investigation in hearing loss. The main modality for investigation is radiological imaging.

This guidance suggests that where someone has asymmetry of hearing with a 15dB difference between the ears, at two adjacent frequencies, then an MR scan of their internal auditory meatus should be performed. A patient who presents with unilateral hearing and tinnitus symptoms, especially if this occurs with numbness of the ipsilateral face or imbalance should be referred to the local ENT service (patients can be referred on a routine basis). Usually, MR scanning is not requested in primary care, unless hearing testing is also available.

It is a feature of the hearing loss in a patient with an acoustic neuroma that they complain of a hearing loss over and above that which is seen on pure tone audiometry. This is because of to the loss of discrimination in a hearing loss due to compression of the acoustic nerve. While a patient may be able to identify a single tone, they are much less able to identify words and sentences, which are complex acoustic patterns.

Treatment

Management of the patient presenting with symptoms of acoustic neuromas is by a routine referral to an ENT service. GPs in general do not arrange MR scanning. This may be necessary, but audiometry usually requires the expertise of ENT and audiology and most patients with these symptoms will end up with an alternative diagnosis and need management of their ear condition.

The treatment of acoustic neuromas depends on the size of the tumour, the severity of symptoms, the patient’s hearing level, patient choice and age. When such tumours become 4cm in diameter in the posterior cranial fossa, raised intracranial pressure can be a threat to life. As the typical growth of an acoustic neuroma is around 1.2mm per year, a patient in their twenties with a 1cm tumour will need treatment due the eventual growth of the tumour, whereas someone in the 80’s will probably not.

There are 3 treatment options:

1. Observation (Watchful Waiting)

Suitable for small, asymptomatic tumours or elderly patients. Regular MRI scans monitor tumour size and growth. The risk of observation is tumour growth and therefore if treatment becomes necessary, treatment will be to a larger tumour.

2. Radiation Therapy

Stereotactic radiosurgery (e.g., Gamma Knife). This is a non-invasive option for small to medium-sized tumours, aiming to halt tumour growth. This treatment does not result in the tumour’s obliteration, but in over 90% of cases, growth is arrested and further treatment is not required. There is a general cut off for tumours of 3cm intracranial diameter, so if acoustic neuromas are detected when larger than 3cm, gamma knife ceases to be a treatment option. As with stereotactic radiosurgery, swelling can result in raised intracranial pressure from tumour oedema.

Fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (FSRT): Used for larger tumours or in patients where surgery is risky.

The risk of radiation therapy is failure to control tumour growth, hearing loss and facial nerve palsy. The risk of inducing a malignant tumour is theoretical and generally not seen in practice.

3. Surgery

Microsurgical removal: The most definitive treatment, often chosen for larger tumours or those causing significant symptoms.

Surgical approaches are translabyrinthine (through the inner ear), middle fossa or posterior fossa.

Any such brain surgery is a major operation with risk of morbidity and mortality and prolonged recovery, with specific risks of facial paralysis, paralysis of other cranial nerves, cerebro-spinal fluid leakage and meningitis, stroke, failure to completely remove the tumour, with possible regrowth and further treatment.

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with acoustic neuromas is good. Rarely now will someone die of this condition. 100 years ago death was the usual outcome, at least for growing or large tumours. Hearing tends to decline with time, with whatever treatment. With surgery, hearing is often lost and is always lost with a translabyrinthine excision of the tumour. Facial nerve function is preserved in almost all gamma knife treatments. With surgery, facial function is directly related to the size of the tumour, so early identification of acoustic neuromas can transform treatment and outcomes.

Mr Gerard Kelly is consultant ENT and skull base surgeon at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.