All things being equal

This site is intended for health professionals only

Tackling health inequalities was always part of the PCN brief, but can they deliver on this huge ask with the extra pressures of the pandemic? Emma Wilkinson reports

In his Build Back Fairer review at the end of 2020, Professor Sir Michael Marmot noted that inequalities in social and economic conditions before the pandemic contributed to the high and unequal death toll from Covid-19. This followed on from his report 10 years before, Fair Society, Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review), which found that health inequalities were widening and life expectancy was stalling. If we do not tackle this now, when will we?

Locally agreed action on tackling health inequalities has been part of PCN priorities since their inception. The service specification for PCNs was supposed to start this year but was delayed by the pandemic and remains under negotiation.

Beccy Baird, senior fellow at The King’s Fund think-tank, says in many areas PCNs are already doing work on health inequalities, listing examples from Surrey to Sheffield to South Lancashire. ‘I think the potential is really significant and I think PCNs are really well placed to respond to the needs of their communities.

‘Bromley by Bow is always talked about as an amazing place in Tower Hamlets where they’ve really thought and listened to communities, but they’ve always been a bit of an outlier. Now you see more and more PCNs really starting to think about how they listen to communities, how they understand what the priorities are.’

What is key, she says, is allowing PCNs flexibility. ‘It’s one of the challenges of how we can balance meeting the needs of communities with what specifications say.’

Poor funding formula

Yet for all the potential and willingness and innovation she has seen in PCNs, everything could be derailed by issues with contracts and funding.

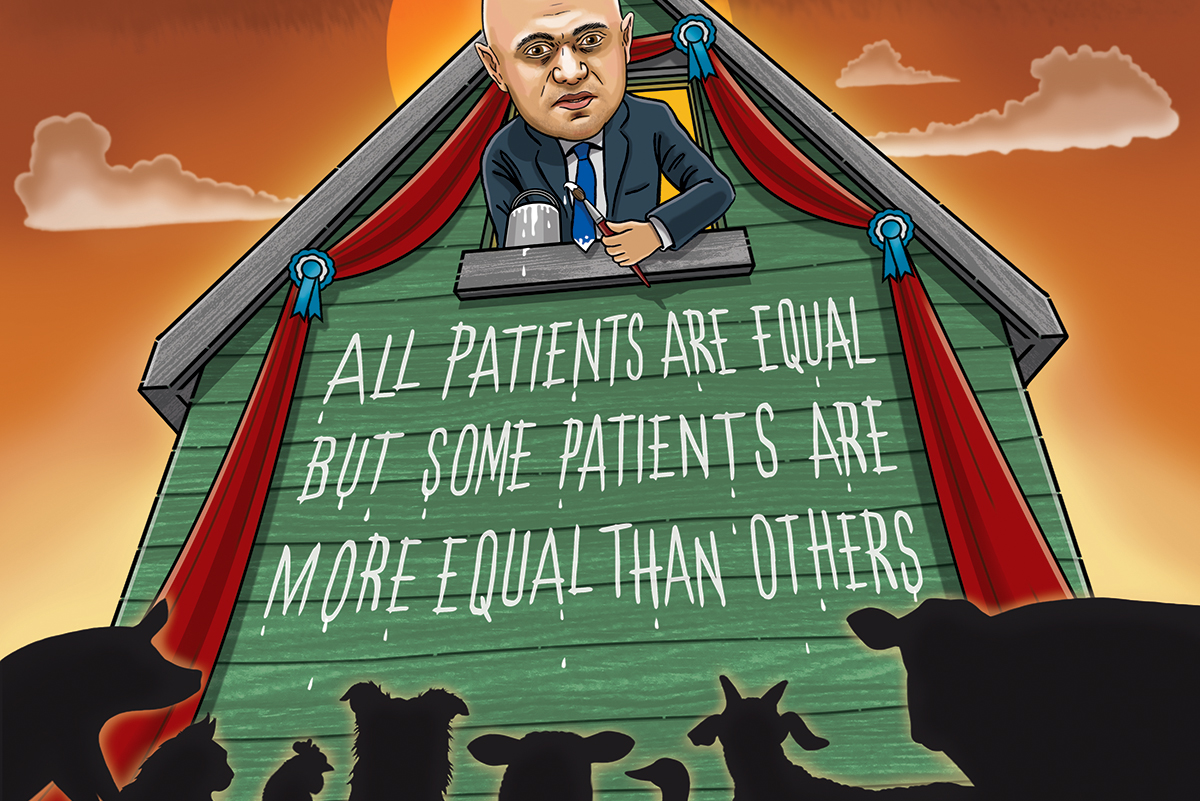

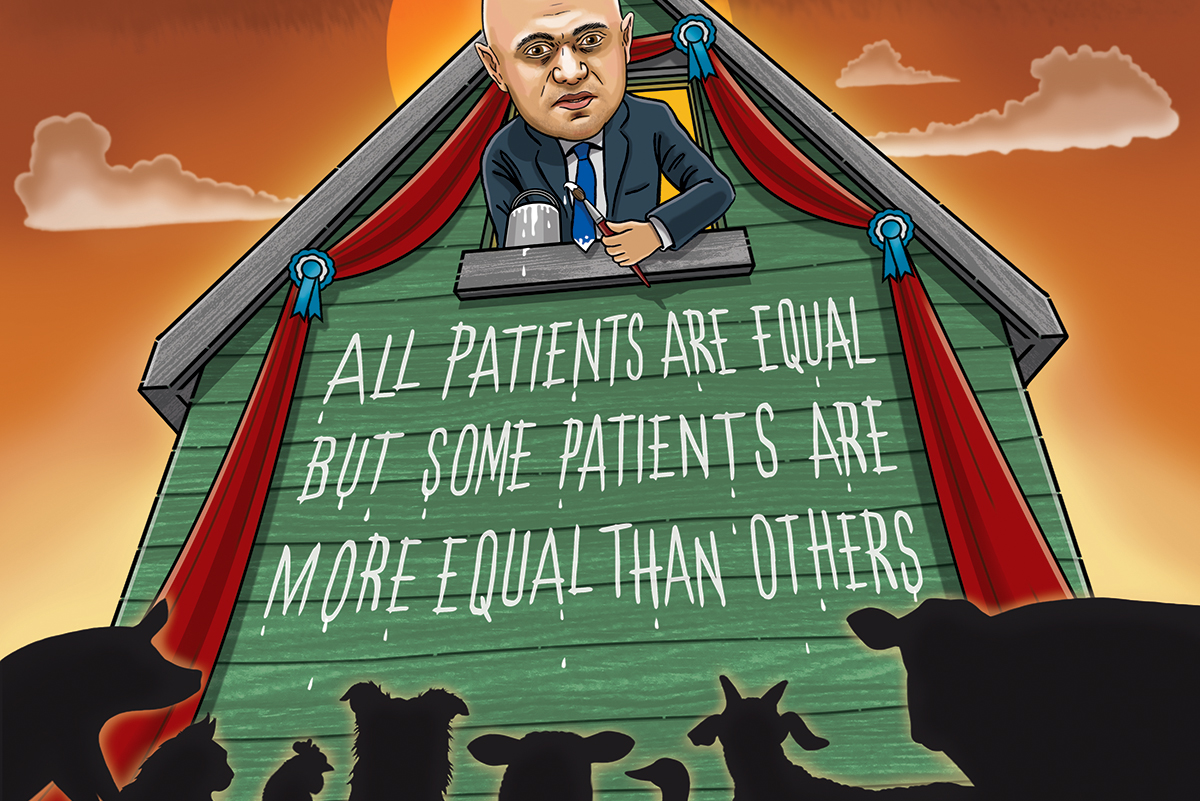

‘The funding formula is pretty rubbish when it comes to deprivation. We can see that through some of the PCN allocations. There are systemic issues in the way the contract works which don’t help people in deprived areas,’ she says, giving the example of wealthier areas getting extra funding because they’ve hit all the targets.

One example of this is a warning from the Health Foundation that the additional roles reimbursement scheme (ARRS) could exacerbate health inequalities because recruitment is likely to be skewed to more affluent areas, leaving those that are already under-funded and under-doctored with even less resource. In addition, the Government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda would only work if that included general practice, according to the Health Foundation’s report Levelling up general practice in England: What should the Government prioritise?.

Dr Hussain Gandhi, clinical director of Nottingham City PCN, knows this all too well. His population is ethnically diverse with high levels of unemployment, homelessness and substance misuse. The PCN most wanted to tackle mental health, which he estimates at 60-70% of GP workload for the three practices in his PCN. But these plans did not fit into the stringent requirements for ARRS roles funding.

‘Funding is often very specific and that doesn’t lead to a lot of innovation. If I had the ability to do anything I would go out and get six mental health workers – and patients would be far better served by having those roles.’

He adds: ‘We wanted a safeguarding coordinator because we nearly have triple or quadruple the number of child protection issues. One of our practices has the same levels of safeguarding as the entire county.

‘We have tried to innovate with the resources we have,’ he says, but inevitably they are constantly hunting for small pots of money.

‘It can only be split so many ways,’ he says. ‘It has to top up ARRS roles or estate. There just isn’t the resource and the stringent requirements of all these pots of money mean you’re constantly looking for workarounds.’

He is becoming increasingly disillusioned, he says, noting that the ratios of GPs to patients change from 1,200:1 to 3,000:1 from the leafy areas to the inner-city areas. ‘We have less resource, both in terms of finance and workforce, and we’re trying to help patients with really complex medical problems but are judged by the same yardstick,’ he says. ‘We were promised local control but that’s not happened at all.’

His PCN’s current focus is a project on patient education for those who don’t speak English, which he says is where they feel they can have the biggest impact right now.

PCNs need better support to tackle inequalities

Baird says that additional support for PCNs will be vital, not least because the NHS workforce is simply exhausted. ‘They’re really tired, they’re really really overworked. Finding the headspace to do this stuff is really challenging.’

In effect, she says, there has not been the infrastructure to support primary care since primary care trusts were disbanded in 2012. The ‘improvement bit of NHS improvement’ that exists for trusts does not exist for primary care, she points out.

‘There are some practical things that systems can do, like providing good data analytics, helping with supporting volunteer programmes and helping with estate,’ she says. She adds that those who have a burning desire to make an impact on improving health inequalities will most likely find a way to get resources and staff.

She also says that the Covid vaccination programme has created many new links between PCNs, community and volunteer organisations and local authorities – and now is the time to capitalise on that.

‘We need to work on local priorities’

For Dr Yasmin Razak, a GP and associate clinical director at Neohealth PCN in North Kensington, west London, the pandemic was not the reason for forging those community links. Four years ago, the area was hit by the Grenfell Tower disaster. ‘We know that communities are the answer,’ she says.

From the north end of the borough to the south, there is a pre-pandemic life expectancy gap of 18 years. Yet there is ‘no extra resource or funding allocated, despite the known deprivation’, she says.

‘I think we’re on the journey with our patients, especially since Grenfell Tower. I think my eyes have been opened; GPs understand the wider social determinants of health. Although we say it’s not really in the GP remit, there is an influence that we can have, there is a voice that needs to be heard and a clear need.’

Health inequalities should be the lens through which we look at everything, she says. ‘For me, a PCN is about providing good quality primary care and everyone having a basic standard and we’re meeting that standard and every surgery in the PCN should get the same outcome. That’s the basic requirement. Then we need to work on local priorities, whatever they may be, and that’s why data must be a driver.

For her PCN, that initially meant diabetes care. ‘It’s a really good thing for PCNs to home in on a particular area. That doesn’t mean they can’t switch to a different area. We did diabetes first, then we switched to respiratory health because the data show there are high smoking rates and poor access to spirometry.’

Graphs show these measures have made a difference, she says. ‘We can’t just look at historic outcomes and say that’s how it always is. We’ve got to gently challenge – and be advocates for our patients.

‘We’re navigating carefully and being careful not to get too involved in the wrong area. We need to keep our remit quite defined.’

The other part of the equation, she says, is patient advocacy and the involvement of community champions, which was shown to its fullest benefit in the Covid vaccine campaign where community champions worked incredibly hard to boost uptake.

But the funding flows have to be sorted, she adds. ‘The truth of the matter is we work until midnight, seven days

a week and that’s quite a depressing inequality in itself.’

No coherent strategy

What is missing for Dr Razak is the link between national strategy and PCNs. ‘There is not enough support organisationally for PCNs. It becomes a survival of the fittest.’

For Dr Emma Watts, a GP partner at Shere Surgery in Surrey, the lack of flexibility in funding streams means her rural practice covering 45 square miles in a PCN with five other urban practices is overlooked. Extended hours, urgent care, a whole host of services are aimed at urban populations ‘and there is no appetite for the PCN to address this’.

Her colleagues are sympathetic and acknowledge the problem, but to develop services that meet the specific needs of their own patients ‘seems to go against the PCN model’.

‘The rules are that we have to plan for everyone in the PCN. It’s too rigid and it increases demands on our practice.’

Clacton-on-Sea in Essex is emblematic of many seaside towns that have seen steep decline over the past few decades. Industries have been lost, leading to unemployment. There are high levels of drug-seeking behaviour and complex mental health challenges as well as obesity and general ill health.

Dr Tanvir Alam, CD for Clacton PCN, says tackling health inequalities is ‘a difficult ask’ in one of the most deprived areas of the country. Most recently, they faced an ‘astronomical’ amount of work to figure out how to manage care homes with their high retiree population, and the work was not reflected by the resource.

‘We are trying our best, we are doing population health management to identify vulnerable groups, but that is a huge body of work. NHS England has given us £3,000 for GP manpower time and admin but there are so many areas to focus on and all are equally important.’

The GP profession as a whole is also coping with dwindling numbers of clinical staff, he adds. ‘The workload is already high, with increased footfall. We’re doing our best to engage with whatever is being asked of us but it is a huge undertaking.’

As the Health Foundation warned, the PCN has had trouble recruiting pharmacists for ARRS roles because the funding doesn’t match market rates.

‘NHS England is being careful. That’s fair because it’s public money but there is no money to be siphoned at this PCN. It’s just one person and an operations manager.’ He is particularly disappointed that there are two GPs representing primary care at the ICS but neither is from a deprived area.

‘Actively listen to residents’

At the opposite end of the country in another abandoned seaside town, Dr Mark Spencer believes PCNs need to take a different approach. His patch in Fleetwood, on a peninsula north of Blackpool in Lancashire, was once a thriving fishing town. But now the community has ‘lost its sense of purpose’. Now, life expectancy is 10 years below the national average and there are high rates of cancer, heart disease, COPD and mental health problems. All of this is getting worse ‘despite very significant investment’.

In 2016, Healthier Fleetwood was set up to give residents back some control. Projects included a singing group, Harmony and Health, and the Men’s Shed, which was set up in response to a spate of suicides that shocked the town. What started as a way to improve social connections resulted in a 20% drop in A&E attendances and acute admissions.

Now every decision in the town, including the council regeneration plan, is guided by residents – they set the priorities, most recently about training and digital skills opportunities.

Dr Spencer’s advice for PCNs is this: ‘Don’t be tempted to come up with your own plan. Actively listen to residents. Starting with the data is important but you need to establish relationships with schools, the voluntary sector and housing associations and it takes time. We don’t just want to reproduce what has happened in the past 10 years. And the role of the CD is to push back against anyone telling them to get it done in the next six months, whether that’s the ICS or NHS England,’ he adds.