This site is intended for health professionals only

Leading through uncertain times is no easy task. Psychologist and team coach Dr Craig Newman explores this issue for clinical leaders.

Although it may be a historic cliché, it is still true that the NHS is striving at a time of great uncertainty.

This is particularly the case for primary care, where the continued name of the game is change, but with new or inflated challenges including staff wellbeing, staff retention, service capacity (within and beyond primary care) and patient frustration.

Change has been a continued presence over the past four or five years and at an unparalleled level.

There has been a shift to PCNs, and while PCNs continue to work on their own design and culture, there is now a focus on neighbourhood hubs. This is alongside wider NHS restructuring and the formation of ICS and ICB cultures. In addition, there is a drive for digital innovation to support service delivery. Everything is moving at an incredible pace.

When there is change, there is uncertainty – and that has an impact on teams and leaders because of the anxiety it causes.

The concept of ‘uncertainty’

The word uncertainty is used often in leadership settings but there are some differences between corporate settings and PCNs.

PCNs, led often by clinical staff, are qualitatively different to leaders in the corporate sector. The main difference is that clinical teams work with uncertainty almost constantly, as their primary function – with serious outcomes when things go wrong.

Patient health and the investigation of diagnosis, along with decisions around response to presenting issues can be perceived as the management of uncertainty. Clinical teams are expert in it and are trained to feel safe with it through developed clinical judgement.

It’s fair to assume that well-developed clinical teams, as a whole, develop a judgement of sorts that supports this type of safe uncertainty. Triaging, assessing, prescribing, referring – all activities that can never be based on certainty of need or outcome. Instead, they are based on best judgement through training and experience.

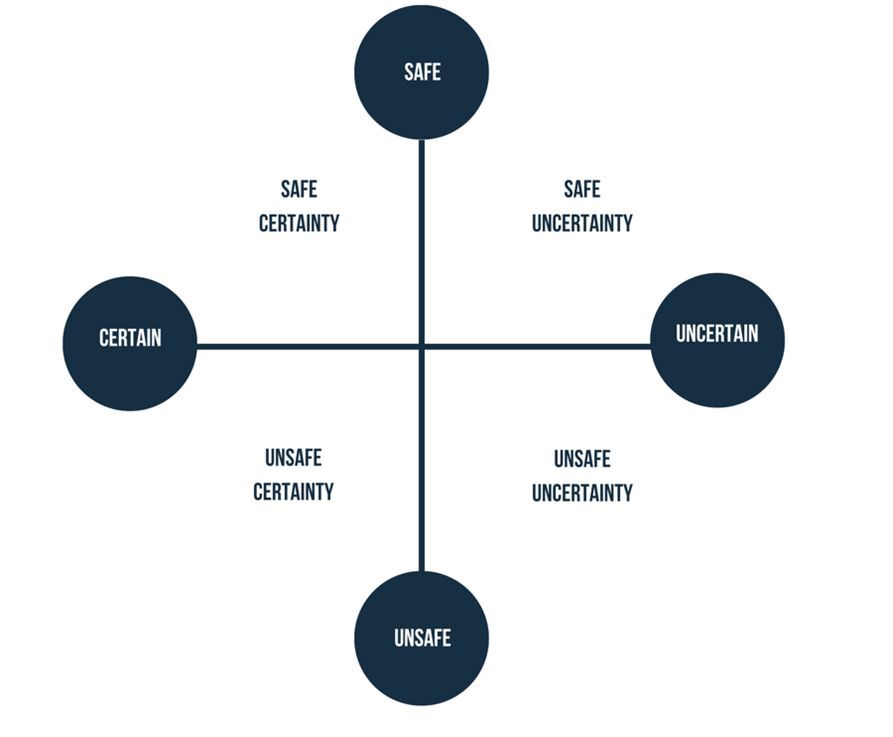

This invites a wider perspective on uncertainty to reveal why such experienced teams become anxious. It can be useful to see the concept of uncertainty and certainty as a matrix (see image below).

In this matrix, each area is a scale and the culture of a team can sit at any point in the white space. In the example of clinical care, we train clinicians to understand differential diagnosis, to synthesis experience and knowledge and to call on the same from peers to make relatively safe-uncertain decisions about patients.

When leading a team through periods of anxiety-inducing uncertainty, we may assume that it is the scale or apparent undefeatable nature of the challenge that is causing the anxiety. The list of challenges can be long and varied – unpredictable change, job insecurity, relentless patient dissatisfaction, the threat of AI, the risk or experience of burnout, or team fractures.

Whatever the challenge, the real problem is a sense of lost safety; uncertainty alone is not anxiety-provoking. When teams are adequately equipped, uncertainty is less of a problem.

How NOT to lead through uncertainty

Leaders are the source of team culture and can, in an attempt to manage uncertainty, inadvertently create cultures that lead to fracture, disengagement or more anxiety. Here are three such approaches that map onto the matrix above:

1. Feeling and acting as a leader(s) that their approach is the safe and certain way (no change is needed), to deliver a team through uncertainty via:

2. Feeling certain of the approach as a leader (despite the evidence), but also feeling unsafe in trusting the team to deliver on this approach:

3. Feeling lost as a leader, in the current context, and feeling unsafe in being able to lead or effect change. An unpredictable leadership style that leads to leadership and team experiences of:

As you read this, you may imprint your own experiences of overbearing, insecure and burnt-out leaders and perhaps how this had led to disengaged, unsafe and fractured teams. It’s a fog any leader can fall into when they are not pausing to observe that a response to create safety is the response that manages uncertainty.

The concept of safe uncertainty was coined by Barry Mason in 1993 (a systemic family therapy) but has relevance for clinical teams (1). Keeley (2009) (2) helps us to understand that cultures can emerge that mistake the false need for uncertainty, in place of a real need for safety. Or, to put it another way, when we feel anxious during times of change and threat, psychological safety within teams is the solution. Any other response to unsafe-uncertainty pushes us to one of the three areas on the matrix listed above.

Realising uncertainty needs safety

So, how does a leader create this safety? There is research that informs the current NHS leadership framework, with a focus on compassionate leadership and compassionate teams – I’d recommend readers review. From our experience with PCNs, primary care leaders and national primary care teams, here are a few tips:

In conclusion, recognise that uncertainty is the most predictable aspect of all of life and work. We can crave certainty, but a belief that we have it will stagnate a team. When we are feeling anxious about the future, we often think it is the uncertainty that is the issue – but if we pause and take notice, we will see that it is the lack of safety that is the problem. For leaders, the challenge is creating safety even in times of uncertainty.

Dr Craig Newman is an award-winning clinical psychologist and team coach who specialises in developing NHS teams and leaders, particularly in primary care. He authored the book ‘Leading Primary Care: Resilience, Team Culture and Innovation’. He is CEO of both a team development service Aim your team and an NHS burnout prevention not-for-profit Project 5.